My Inspiration for Writing Smitten

He slid into my room, unnoticed, while I placed a last photo into its 4-cornered slot. I sat on my childhood bed in a room I had once shared with Mary, my older sister. But now she was gone, so I was pulling together the few pictures I had of her, along with colorful hand-painted postcards sent to me from her travels, and pictures of her in the Louisville Courier Journal—as lead in a school play; victorious captain of the Amazons, a field hockey team; at graduation from Louisville Collegiate School wearing her long white gown and holding a spray of roses, the color uncertain in the black and white photo.

I rested my hand gently on the last page, feeling my sister, afraid that closing the heavy leather scrapbook would unsettle the memories as fragile as a whisper.

My father may have stood there a minute or two before I heard his labored breathing, already raspy, alerting me to his presence. Then I smelled the sweet fragrance of a surgeon’s well-scrubbed hands, a scent that lingered though it had been years since his last operation. I turned the scrapbook so he could see it from where he stood behind me.

Without speaking, he took it and placed it in the center of my large oak desk. He turned back to the first page and I heard his breath catch. The light from my window had fallen diagonally across a photo of infant Mary cradled in his embrace, her lacy baptismal dress trailing over his arms, descending almost to the floor. It is the gown made by my great Aunt, a nun, and worn by me, my younger sister Elizabeth, and then my daughter, Kyla. Tradition handed down and a thought pierced my heart: our deathbed should be encircled by our children and grandchildren, and never should a parent have to lay flowers at a child’s grave, the utter disrobing of order as it should be.

I watched him turn each page with a lightness of touch as if the images might disintegrate into ashes and disappear as Mary had. When he was through, he looked at me with filmy eyes, and, unabashed, with the back of his hand, wiped a tear from his cheek. He forced his lips into a suggestion of a smile and nodded a muffled “humph” signaling some finality, “it is done.” He stuffed his hands in the pockets of his kaki pants and walked out with the awkward gait of a graceful man who had been drinking.

Later that evening he sat in the family room in his straight backed chair, good for his ailing back, and stared at the dulling white noise on a TV encased in a 60s style cabinet—things lasted in my parents’ home and unless it had broken beyond repair, which was rare, it remained; like the bumpy aluminum pots that had belonged to my grandmother, or the gas stove that had been there for as long as I could remember. My husband had said it was like walking into a museum, but to me it was comforting, an oasis of stability in a tempestuous and often demanding world.

“You might want to see these,” he said handing me a thin rectangular box, one of three, the other two I saw stacked on his mahogany side table. The box was yellowed with age and one corner had ripped at the seam. I opened it, surprised at what it held, and couldn’t resist running my hand over the rough black leather of a journal that had a remarkable sheen of newness. Everett G. Grantham M.D. was embossed in gold on the bottom right.

I sat on the sofa beside him and turned the pages of the war time journal, feeling the rich quality of the paper, while taking in the familiar cursive of a writing style both formal and elegant, and not often seen today. At the young age of twenty-nine he had become Chief of the largest Neurosurgery Center in the U.S. during WWII.

I stopped at a date that drew my attention: October 30. My heart pounded as I read:

About 4:30 am while we were waiting in the reception room of the Philadelphia Lying-in Hospital, a nurse came in with a baby and said, “Major Grantham?” I said, “yes” and she said, “Here she is.” She weighed 8 pounds and was a perfect specimen. Not a mark on her head, not even the usual swelling they have. Carmel came down around 5 am . . . and looked wonderful. She was quite elated and no signs of exhaustion at all. I was certainly proud of her. I had to leave about 6:30 am and drive back to the hospital where I had an operation to do [Thomas England General Hospital in Atlantic City, Neurosurgery center for WWII]. By noon, I was about dead, the excitement, pacing the floor, loss of sleep and the operation really fixed me. I went over to my room for a 2-hour nap and then caught the train for Philadelphia again.

October 31 Carmel is feeling good. The baby has lost a few ounces but appears to be in fine shape. When I look at her I can hardly realize she is my child. I find myself resolving to be a better person, to work harder that I can make myself more worthy of she and her wonderful mother. I have more desire to accomplish something worthwhile and to succeed economically than ever before in my life.

I closed the journal and felt him watching me but I could not look up.

“I’ll just keep these here,” he said, placing the other two on the bottom shelf of his table. I put the third one in its box and placed it on top of the other two.

“You can have them whenever you want. Carmel gave me the first one when I joined the army in May of ‘42. She thought it would be good for me to keep a medical journal and it started out that way. But I couldn’t help writing mostly about what was happening in our lives; and the war, of course. You might find it interesting some day.”

I would, but I wasn’t ready that day. Over the next several years, whenever I visited, I would pick up a journal and read passages here and there. I wish I had asked questions and taped answers. But now that is not possible. Perhaps they were meant to be read without commentary or analysis by my father, to unfold as a remarkable window into the past, one that would lead me on a long journey of discovery.

In the late 90s I was offered another invitation into their world of the Forties, of wartime life in the states and my father’s service in the army, of the New York celebrity scene of which my mother was a part. It was a sad visit home. My mother, in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s, had been in a nursing home for six months while my father continued to live at home, though he was already a year beyond the date his doctor said he could live with inoperable lung cancer.

I returned from the nursing home, weary and depressed. It was a lovely place, well run, but I adored my mother and today it was hard to talk and pretend, knowing she would have no knowledge of my visit or our conversation once I had left. She did know me, and though she could only say a few words, she had asked, “Kyla?” my daughter’s name and I had replied, “She is working on Martha’s Vineyard, Mom, and couldn’t come this trip.”

She’d smiled, her brilliant blue eyes shining with love and understanding, and stroked my shoulder length blonde hair.

Her pleasure and joy at seeing me only made the pain of leaving worse. She was in Louisville and I was a corporate attorney in Boston, facing financial pressures of a child heading off to college.

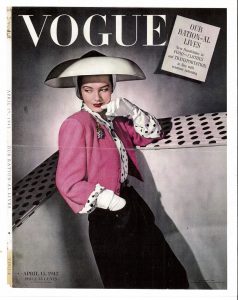

The moment I entered our house, I heard the sexy crooning of the clarinet, the soft swish of brushes against cymbals setting the jazzy tones of Swing. I walked into the family room and found my father gazing in a trance at a picture of her on the wall, an enlarged 2 x 3 foot photo of the cover of a September 1941 Ladies’ Home Journal.

It was one of his favorites and I would often find him staring at it, unwavering and with such intensity, I asked one day what he was thinking.

“I’m communing with her. We always did know each others’ thoughts.”

In the photograph she was wearing a nurse’s uniform, a navy blue cape with red lining, a red cross sewn on the front, white blouse, and white cap with the same red cross in the center. Her parted lips were colored red, but other than that, she wore no make-up, or jewelry. Her deep blue eyes were luminescent from the triple reflected flashes of a photographer’s camera. The v-neck of the blouse drew one’s eyes to the alabaster skin and elongated contour of her neck. It was an exquisite photograph, yet she looked unattainable, her gaze focused above the viewer’s eyes.

Today he was wearing a navy blue cardigan, patched by her on the elbows with navy leather. He had a letter in his hand, resting on his lap. I sat and it took him a few minutes to know I had entered.

He smiled with sad eyes. “How was she?”

“Fine. She understood who I was.” I knew he couldn’t visit her often. The shock of it drained him and he already looked a ghost of his former self. He had been a handsome, well-built 6’1” but now weighed only 130 pounds, almost too frail to walk. His pallid skin clung to the angular bones in his face, the hollows of his cheeks so deep that his blue eyes appeared too large and had a haunted quality.

He lifted his hand with the letter and let it drop back into his lap, as if too exhausted to hold up a filmy piece of paper.

“I found these in the back hall closet,” he said and I followed his eyes to the large box at his feet. I almost gasped imaging how he must have rummaged through the cluttered closet and then found the strength to drag the box down stairs. I kneeled beside the box and opened it—hundreds of letters in my parents’ handwriting, addresses to army bases, to New York, Louisville, Georgia, New Orleans, dates from 1940 to ‘45. I picked up a handful, pouring over the places and dates. I looked at him, “There must be hundreds . . .”

“Over a thousand,” he said with a satisfied smile. “My mother saved all of Carmel’s letters to me and when Mama died, I brought them here. Carmel must have added her own to the pile because I found a bundle of mine to her when I was stationed in the Pacific. God, the things I thought important back then.” He chuckled and I smiled—I rarely heard him laugh anymore.

“I want you to have them,” he said. “And take these journals, too.” I eyed him cautiously. He’d never been so insistent.

“Are you sure you want me to take them home with me now?” I asked.

“Yes, certainly. I have all the memories I need and–” nodding toward her picture on the LHJ cover, “she still communes with me.”

I put the clump of letters I was holding into the box and settled back into the flowery pillows on the hard sofa, another anachronistic piece of furniture. “Tell me again about when you met, about New York, and life in the army.”

He sighed, then took a deep breath and looked up at the ceiling, where to begin, he seemed to think. “I was smitten from the moment I saw her . . . ”

The next day at the nursing home I found my mother in her wheelchair with other residents, everyone in their own world listening to a scratchy record from the Forties. I watched, smiling, as my mother tapped her foot rhythmically to the undertone of the saxophone. Oblivious to me and others, my mother swayed her hands in perfect harmony to the Glenn Miller melody, her shoulders and body soon following suit.

A memory, a dream that had all but forsaken her was resurrected for the moment.

Suddenly, she caught my eye and fell back into her wheelchair, laughing self-consciously. As I approached, she put a finger to her mouth as if to say “hush” but the words didn’t come. She smiled like a schoolgirl who had pulled a mischievous prank, but her eyes sparkled with joy, as beautifully blue as in her youth.

She needn’t have worried. The others stared out the window blissfully vacant, rocked to the music, or tugged obsessively at a distraction in their lap—a shawl, a trinket, a little treasure of their own.

My mother’s attention span was quite short, and so, forgetting any embarrassment, she started swaying again and humming softly out-of-tune under her breath.

She seemed more at peace here than at home where the burden of remembering weighed heavily upon her. The lines in her face had softened. At home she knew she was supposed to be a wife and mother, but she couldn’t remember how. Here she was loved for her essence, her gentility and charm, a favorite of both the staff and residents alike.

I knew all the residents. Everyone had a story to tell and I would let myself be whomever they wanted–a child who never visited; a deceased spouse still held in conversations; a sister, mother or friend who, for whatever reason, had disappeared. Their minds never ceased to amaze me, leaping from one vivid memory to another. Recent events were soon forgotten, but the first date, or the kiss of a young lover were memories relived daily in bright, panoramic display.

I looked up to see an old family friend, Mr. Philip Williams, shuffling across the shiny linoleum floor with the help of a walker, never taking his eyes off my mother. Like all the men in the Home, he gravitated towards her, drawn by her classic beauty and Southern charm.

Lowering her eyes in a coy manner, she smiled, coquettish yet innocent and glanced at me to see if I had noticed her admirer. I nodded. My daughter had tagged her “a guy magnet,” referring to her captivating allure.

Aunt Vickey, my mother’s younger sister and best friend, had told me that was always so. And certainly, her charismatic charm had held true for as long as I could remember. Even with her mind ravaged by an insidious disease, she maintained her glamour and an aura of elegance, her head held straight and her posture, that of a ballerina. Yet, her genuine warmth and graciousness lent her an air of accessibility.

She was always considerate of others, and not even the gray mist of Alzheimer’s could diminish that. The staff loved her. One of them told me she would “smoke” her cigarettes of straw and politely blow the smoke away from anyone standing near. They got a kick out of that and occasionally took her into the backroom where she could have a real cigarette. I had let her do the same at home.

I smiled watching an expression come over her that I knew so well. She lowered her lids while arching her brows, which suggested a cool hauteur, yet the perpetual half smile softened her expression, making her appear serene rather than austere.

Today, she reached out to stroke my hair, fond of the natural blonde color yet approving of highlights I’d added.

She smiled but words did not come, making me ache for a conversation I knew we’d never have again:

“Don’t you think blonde streaks would make my face brighter?” She’d ask, touching her beautiful auburn hair burnished with amber and gold.

I’d smile. “Maybe, but I think gold tones would be more flattering.” I knew she’d never do it.

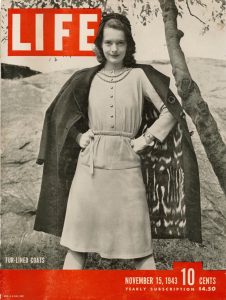

I was anxious to show her a letter or picture, so I stooped beside her fumbling in my purse. My hand was shaking but I managed to unfold the beautiful picture of her on the cover of Life magazine and place it on her lap. I watched her face closely, imagining her feelings of joy and recognition.

She picked up the picture, looking at it as if it were someone else, then smiled at me and handed it back without a change in her expression. Tears welled up in my eyes. I opened the letter, intending to read it to her, but I choked on the emotion.

Trying to compose myself, I looked down at the letter, dated 1940 and written on a deposit slip of the Kentucky Title Trust Company where my mother had worked. Her choice of stationery made me smile again, thinking how carefree and spontaneous she was. I read it out loud.

Hello Honey,

Here I am again. It was wonderful being with you last night. You’re not easy to forget the next day. Or any time for that matter. A fine place this is, they don’t even have writing paper for us. People keep coming up and giving me money, it’s such a bother.

At the risk of repeating myself, I will say again you are sweet, adorable, wonderful and handsome, in spite of your summer hair cut. I’m no good for anything today but to think about you. Which is the worst thing I could do. Well I will now mail this fan letter.

Call me up dammit. Carmel

Tears trickled down my cheeks. Surely, this letter would touch her heart and jog a memory, maybe bring forth tears.

She reached out to touch my tears, smiling softly, then turned back to the window. Slowly, she began to sway to the tune again. And my heart broke.

Mr. Williams had finally reached his destination and stood before my mother with a look of awe: the exquisite bone structure, the elegant curve of her neck, and those unbelievable deep blue eyes.

But the distant look in her eye told me that we had lost her again to the music of the Forties. Where was my beautiful mother now? Perhaps she was with her celebrity friends at the Stork Club, or in the backroom of Sardis with Gene Kelly and his entourage, or maybe transported back in time to that Christmas dance in 1939, so long ago, where she had first met Everett.

After my parents passed away, my Aunt Vickey and I talked weekly, laughing over her wonderful anecdotes of growing up with my mother, her best friend and confidant for a lifetime. She often told me I reminded her of my mother. I couldn’t see it, but I was flattered.

When I was in Louisville for my younger sister’s funeral, Aunt Vickey took me on a special tour of their childhood neighborhood.

I saw the backyard where their father built a stage for plays my mother wrote and directed; I followed their childish voices, giggling under the playground bleachers in Central Park, a stolen kiss and secret passwords, a cigarette, curls chopped off into a bob like Adele Astaire’s, Fred’s beautiful sister and dancing partner; or pouring over their beautiful Aunt Maisie’s Vogue Magazine.

I heard the shouts of Carmel, Vickey and little Peg, felt my mother’s victories and heart breaks, the echoes of the past reverberating in my soul. Her voice became mine and the echoes of both resonate in my daughter.

As I read the letters and diaries, I remembered once again my mother’s strength and courage, her strong will and passions. I wrote my book Smitten inspired by my parents’ letters, over a thousand, and four years of my father’s war journals.

Their story opens a window into a momentous time for our country: the war and deprivations, the celebrities and culture of a fascinating era, and the story of one couple who struggled against many odds — religious and class differences, Everett’s determination to be sent to the frontlines, Carmel’s extraordinary fame, and wealthy suitors trying to pull them apart. It is also a story of my mother’s empowerment in a day of restricted opportunity for women, her meteoric rise to fame, and ultimately what she did for love.